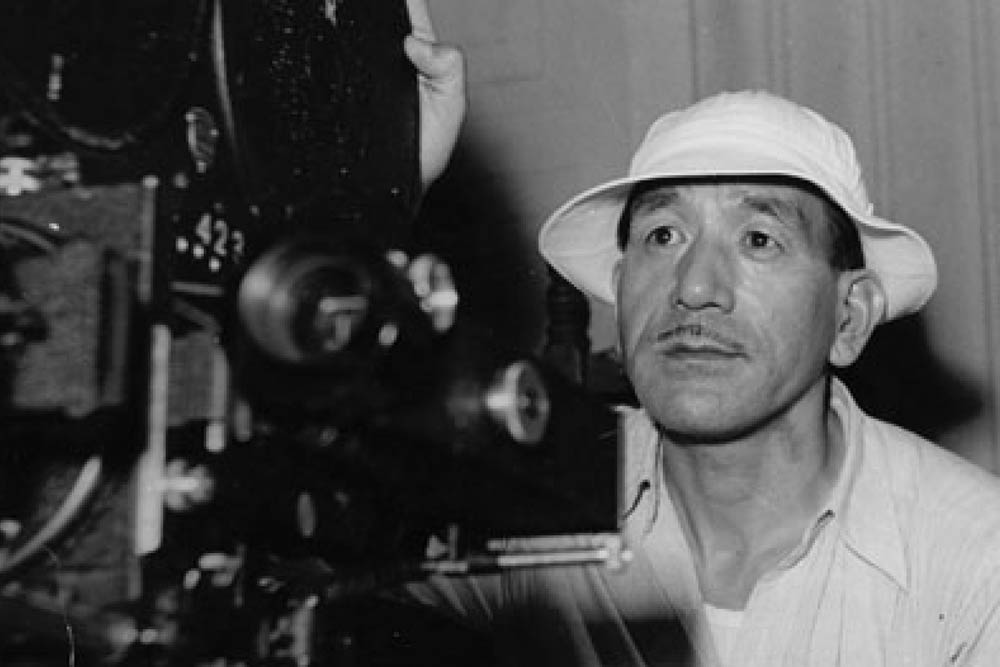

Yasujirô Ozu

Biography

Yasujirō Ozu a Japanese director and screenwriter (Tokyo, 1903 - Tokyo, 1963). A merchant's son, strongly attached to his mother, has been interested in foreign films, especially American films, from his youth. In 1923 he was employed by Shochiku Studio as an assistant cinematographer. He first acquired directing knowledge from K. Ushihara, then he was an assistant to the comedian T. Okubi. He made his directorial debut with his only jidai-geki film Sword of Penitence (1927; first collaboration with screenwriter K. Nod). He then directed mostly comedies for several years, and in the 1930s, his films emphasized social engagement (with frequent references to American melodramas). After World War II (in the most respected period of his creativity) he places the social context in the background of family relations. Ever since the tragicomic Body Beautiful (1928), with the unemployed hero posing to his painter wife, he becomes an influential representative of the classic fabulous style, while with the film I Graduated, But… (1929), and the motives of the hero's social limitations (unemployed, living in a cramped space with his mother and girlfriend) he gradually develops a more personal version of this style. The layered drama The Life of an Office Worker (1929) is often considered his first film in the shomin-geki family genre, in which he made most of his most acclaimed works. His other noted films in this period were also Tokyo Chorus (1931), a drama with comedic elements about unemployment and a comedy I Was Born, But.., with effective children characters. A favorite of Japanese critics, commercially more and more successful, Ozu is gradually emphasizing the connection of the whole with narrative and visual leitmotifs, and he is decreasing his use of rhetorical editing solutions and a dynamic camera. He also develops a recognizable visual identity by low positioning of the observation point and discreet use of telephoto lenses, but still most often addresses topics of interest to the wider community at a given moment, relationships outlined by the genre and production guidelines of Shochiku studios.

His first sound film The Only Son (1936) is a pessimistic drama in the popular genre haha-mono (films about sacrificial mothers). Followed by his military service (1937-39) he expresses his preference for serious dramas in the films Brothers and Sisters Of The Toda Family (1941) and There Was a Father (1942). Hired for state propaganda, he was sent to Singapore to make a film that he didn't finished. In 1945 he spent half a year in British captivity. He then directed A Hen in the Wind (1948), Late Spring (1949) and Early Summer (1951), an anecdotally told film about one family, and his most famous work, Tokyo Story (1953). A layered analysis of family relationships, elaborate characterization, an elegant and slightly anxious atmosphere and an unobtrusive lyricism distinguish Early Spring (1956), with the motive of adultery, and Equinox Flower (1958), his first color film, about a father and daughter disagreeing on her marital choice, while his tendency to process motifs from his own films is most evident in Floating Weeds and Late Autumn. In The End of Summer (1961) he portrays complex relationships in a number of families, while his last film An Autumn Afternoon (1962) focuses on the relationship between daughter and father. In the last phase, he renewed his preoccupations from his early period of creativity (eg elements of comedy), and although at first he was particularly inspired by American cinema, he gained a greater reputation in the West only posthumously. He strictly controlled photography, set design, acting and other components of his films, working with permanent collaborators (screenwriter K. Noda, cinematographers H. Shigehara and Y. Atsuta and actors Ch. Ryu, T. Saito, S. Hara). He has influenced many Japanese and foreign directors through his recognizable atmosphere, motives and actions (eg disobeying ramp rules and tightly tying frames with similar content), while W. Wenders feature documentary Tokyo-ga (1985) deals with the Tokyo Story. P. Schrader described Ozu's style as transcendent, D. Bordwell and K. Thompson call the careful structuring of his films "parametric storytelling," and he was appreciated by Japanese critics from his very beginnings (six of his films were first on the annual lists of magazines Kinema Jumpo). The sense of unity of his opus is strengthened by the repetition of the names of the characters, often in the interpretation of same actors and with a similar function in the story. Although he was probably the most prominent director of family dramas, he never got married. His other major films: Passing Fancy (1933), Woman of Tokyo (1933), A Story of Floating Weeds (1934), The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice (1952), Tokyo Twilight (1957), Good Morning (1959).

N. Gilić / from Filmski leksikon

Festivali i Nagrade

Asia-Pacific Film Festival 1961 - Najbolji film (Kasna jesen) / Blue Ribbon Awards 1952 - Najbolji redatelj (Rano ljeto) / British Film Institute Awards 1958 - Trofej Sutherland (Tokijska priča) / Kinema Junpo - Najbolji film (Rano ljeto, 1951. / Kasno proljeće, 1949. / Braće i sestre Toda, 1941. / Priča o plutajućim travama, 1934. / Prolazni hir, 1933. / Rođen sam, ali…, 1932.) / Mainichi Film - Posebna nagrada za postignuće u karijeri / Najbolji film - Rano ljeto, 1952., Kasno proljeće 1949. - Najbolji film, Najbolji redatelj i Najbolji scenarij / Online Film & Television Association 2017. - Hall of Fame;

Films

Okus zelenog čaja s rižom

Ochazuke no aji, Japan, 1952., feature film

A childless middle-aged couple faces a marital crisis. → more

Plutajuće trave

Ukikusa, Japan, 1959., feature film

The head of a Japanese theatre troupe returns to a small coastal town where he left a son who thinks he is his uncle, and tries to make up for the lost time, but his → more

Rano proljeće

Sôshun, Japan, 1951., feature film

Noriko is twenty-seven years old and still living with her widowed father. Everybody tries to talk her into marrying, but Noriko wants to stay at home caring for her father. → more

Tokijska priča

Tôkyô monogatari, Japan, 1953., feature film

An old couple visit their children and grandchildren in the city; but the children have little time for them. → more